Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/nv/

Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/nv/

Lesson Plan

Photoperiod Phenomena (Grades 9-12)

Grade Level

Purpose

Students will understand how photoperiodism impacts plants and animals in the environment and learn how egg farms use this science to manage the laying of eggs by their hens. Grades 9-12

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Engage:

Activity 1: Explaining Photoperiodism

- Blank sheet of paper or interactive science notebook, 1 per student

- Photoperiodism Notebook Cutouts, 1 copy per student

- Scissors and tape or glue

Activity 2: The Science of Egg Laying

- Animals Who Lay Eggs image

Vocabulary

clutch: a brood, or a group of eggs incubated together

molt: a loss of plumage, skin, or hair; a regular feature of an animal's life cycle

photoperiodism: the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night

protein: an essential nutrient responsible for building tissue, cells, and muscle

Did You Know?

- In 2019 the average American ate 287 eggs per year.1

- At about 15 cents a piece, eggs are the most cost-efficient food for delivering protein to the U.S. diet.2

- Hens can lay up to 1 egg per day. It takes approximately 24-26 hours for a hen to produce an egg.3

Background Agricultural Connections

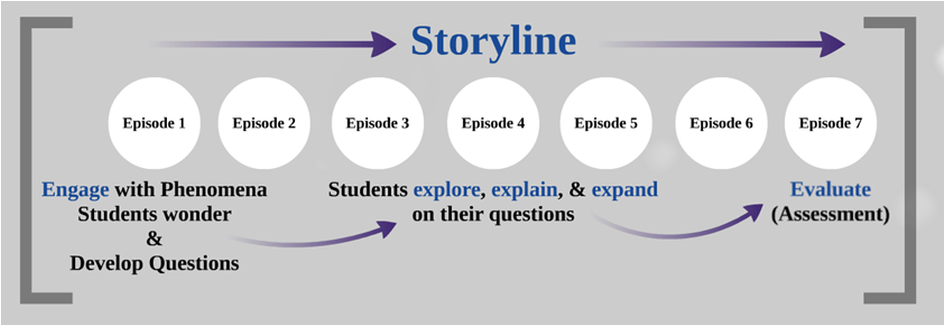

This lesson can be nested into a storyline as an episode exploring the phenomenon of photoperiodism. In this episode, students investigate the question, "Why do hens lay more eggs in the spring and summer than they do in the fall and winter?" Phenomena-based lessons include storylines which emerge based upon student questions. Other lesson plans in the National Agricultural Literacy Curriculum Matrix may be used as episodes to investigate student questions needing science-based explanations. For more information about phenomena storylines visit nextgenstorylines.org.

Protein is an essential nutrient in our body responsible for building tissue, cells, and muscle as well as making hormones and anti-bodies. Sources of protein include milk, yogurt, meat, beans/pulses, and eggs. One egg has around 6 grams of protein. Eggs have been consumed by humans for thousands of years. Eggs are laid by many species of birds, reptiles, and fish. However, due to the ease of raising chickens (compared to other egg-laying species) and the amount of eggs a hen can produce, eggs from chickens are most commonly consumed.

All species of chickens lay eggs. The size and color of the egg varies by the breed of the hen. Egg shell colors typically range from white to deep brown. Hens with white feathers and ear lobes lay white-shelled eggs. Hens with red feathers and ear lobes lay brown eggs. Breeds of chicken that lay white eggs are typically smaller and eat less. This makes white eggs more cost efficient to produce and typically cheaper than brown shelled eggs. There is no nutritional difference between a white- and brown-shelled egg, but some consumers still prefer one shell color over the other. For a lesson plan discussing labels and consumer choices, see Weighing in on Egg Labels, Supply, and Demand.

Hens begin laying eggs between four and six months of age depending on the breed and size of the chicken. Smaller breed hens start laying sooner than larger breed hens. Chickens do not need to be in the presence of a rooster to lay an egg. Farms raising eggs for consumption do not house roosters because there is no need to produce a fertile egg. In the wild, a hen will lay an egg per day until she has a clutch of eggs (10-15), at which time she will "set" on the eggs to begin the incubation process and hatch her eggs 21 days later. When hens are raised on farms, the eggs are collected each day. This stimulates the chicken to continue laying an egg per day.

Many factors impact a hen's production of eggs including her age and body condition. Another important factor is photoperiodism which is the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night. This phenomenon occurs in both plants and animals when the length of day (light) and night (darkness) triggers a specific response in the plant or animal. For example, a poinsettia plant is triggered to flower when the days are short and the nights are long. Sheep and goats begin their estrus cycle in the fall when the days get short. In contrast, horses begin their estrus cycle in the spring when the days are long. Hens are also impacted by photoperiodism. Egg production decreases and may even stop in the winter when the nights (darkness) are long and days (light) are short. Egg producers can manipulate this natural response by adding lights to their hen houses to simulate 14 hours of daylight in their environment. This artificial light will interrupt the natural molting process hens (and all birds) go through as part of a natural life cycle. The molting process is triggered by shorter days, cooler temperatures, and food scarcity. A molting hen stops egg production, loses her old feathers, and regrows new feathers. Chickens kept for commercial egg production have a different molting pattern due to a lack of seasonal environmental differences (primarily light, but also temperature) in commercial hen housing. However, just as egg farmers can simulate environmental conditions for egg production, they can also simulate conditions to induce their flock to molt by decreasing light. Molt can be induced for the entire flock simultaneously allowing hens to grow new feathers, rest from egg production, and allow their reproductive systems to rejuvenate; all leading to a longer life and more efficient egg production.4 Farmers can intentionally stagger the molt of their flocks, allowing for a steady of supply of eggs throughout the year rather than a seasonal supply.

Egg laying farms vary widely by size and production style (conventional, cage-free, free-range, etc.), but all large-scale farms use the science of photoperiodism to manage their hens' egg production.

Engage

- Start with a statement like this, "A friend asked me if I knew why her backyard chickens were laying fewer eggs in the fall and virtually none in the winter. What do you think? Can science help us to understand this phenomenon?" View Egg Farms Prezi with the class. At the end of the Prezi, highlight this phenomenon for investigation: Chickens lay more eggs in the spring and summer than they do in the fall and winter.

- Note that phenomena are observable events and that science is a tool for phenomena investigations.

Explore and Explain

|

This lesson investigates the phenomenon of egg laying. Natural phenomena are observable events that occur in the universe that we can use our science knowledge to explain or predict. Phenomenon-Based Episode: Why do chickens lay more eggs in the spring and summer than they do in the fall and winter? |

Activity 1: Explaining Photoperiodism (Episode Questions 1 and 2)

- Give each student one sheet of blank paper or have them open to a new page in their interactive science notebook.

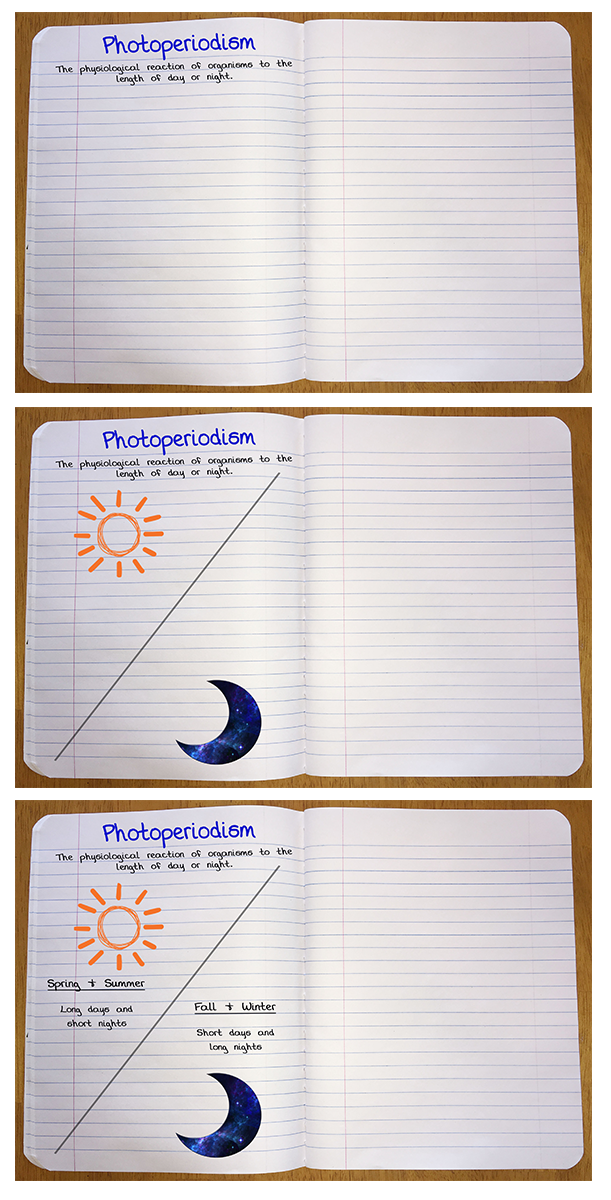

- Instruct students to title the page with the word "Photoperiodism" and record the definition (the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night). Clarify that photoperiodism takes place in both plants and animals.

- Have students draw a diagonal line from the top right corner of their page to the bottom left corner. Draw and color a sun on one side of the line and a moon on the opposite side to signify day and night. (Display image for illustration.)

- Ask students, "How can sunlight impact plants and animals?" Follow up with the question, "Can darkness also impact plants and animals?" Allow students to draw from their own background knowledge and observations to offer answers.

- Next, ask students to think about the length of day (amount of light vs darkness) in the spring and summer compared to the length of day in the fall and winter. Is there a difference? (Yes, daylight is long in the spring and summer and short in the fall and winter due to the rotation of the earth around the sun.) Have students record in their notebooks that spring and summer have long days and short nights while fall and winter have short days and long nights.

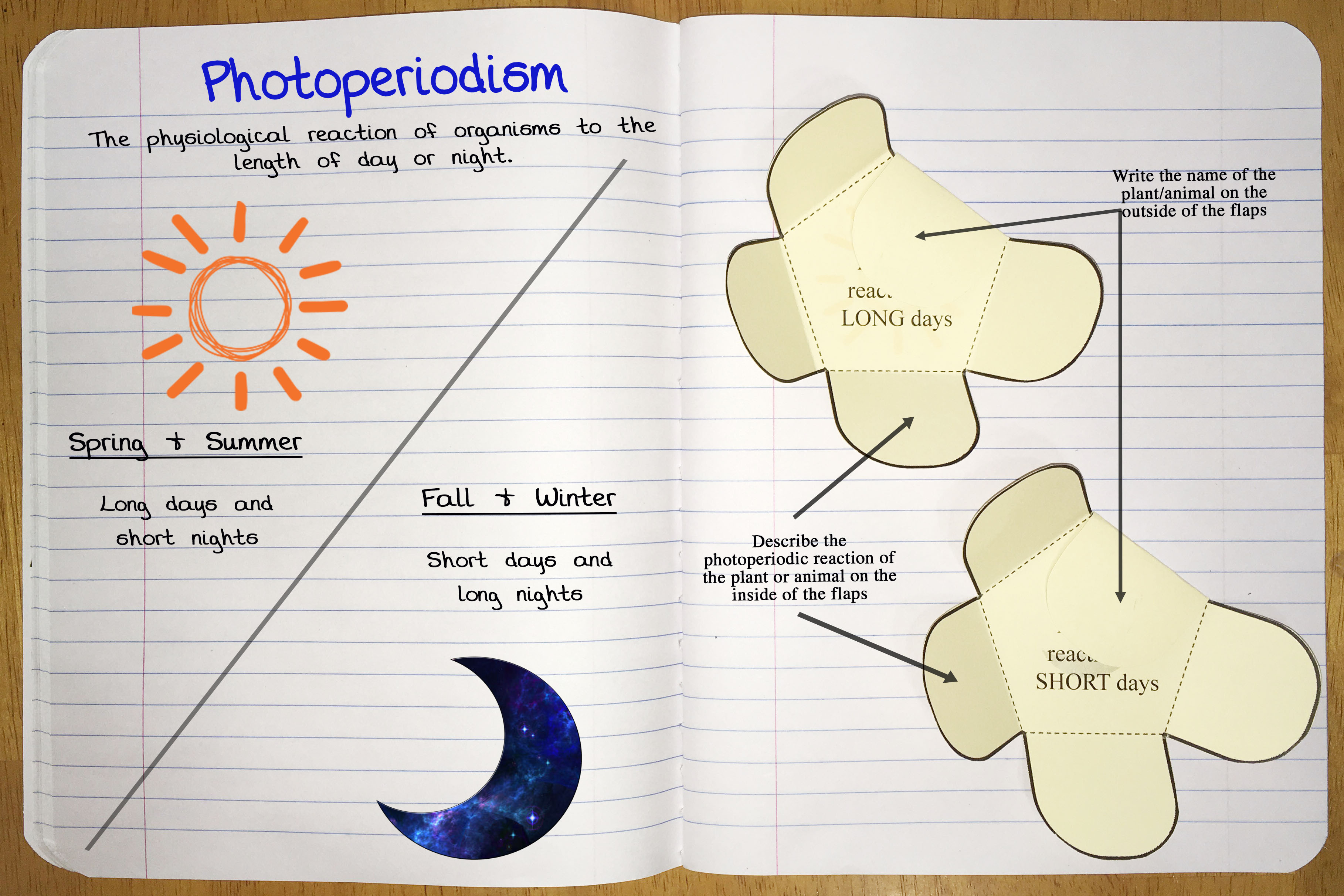

- Give each student one copy of the Photoperiodism Notebook Cutouts. Instruct students to cut out each diagram and place it on their note paper or in their science notebook.

- Assign as homework or allow students time to research examples of photoperiodism in nature. Students should find five examples of plants or animals reacting to long days and five examples of plants or animals reacting to short days. Write the name of the plant or animal on the outside of each tab and describe the photoperiodic reaction on the inside of the tab. Many examples exist in nature. A few examples your students may find include:

- Female sheep and goats only have an estrus (breeding) cycle when the days are short.

- Female horses only have an estrus (breeding) cycle when the days are long.

- Poinsettia plants flower and their leaves turn red when the days are short.

- Chrysanthemum plants flower in the fall when the days are short.

- Pea, lettuce, and wheat plants will only flower when the days are long.

- After the notes page is complete, draw your students' attention to the original phenomenon question. "Why do hens lay more eggs in the spring and summer than they do in the fall and winter?"

- Ask, "Could egg production in hens be influenced by sunlight?" (Yes. Hens will naturally slow their egg production as the days get shorter in the fall and may even stop producing eggs in the shortest days of winter.)

|

Three Dimensional Learning Proficiency: Crosscutting Concepts Patterns: Observed patterns in nature guide organization and classification and prompt questions about relationships and causes underlying them. |

Activity 2: The Science of Egg Laying (Episode Questions 3 and 4)

- Ask students, "If hens slow or stop the production of eggs when the days are short, why can we purchase eggs at the grocery store year-round?"

- Explain to students that egg farmers have various types of housing for hens that are specially engineered with automatic lighting. When the days begin getting shorter, the lights turn on at dusk to mimic a long summer day. This results in hens sustaining their egg production through the winter providing a year-round supply of eggs. For more information about how hen housing is designed to meet the needs of laying hens and solve the problem of photoperiodism, see the lesson Hen House Engineering.

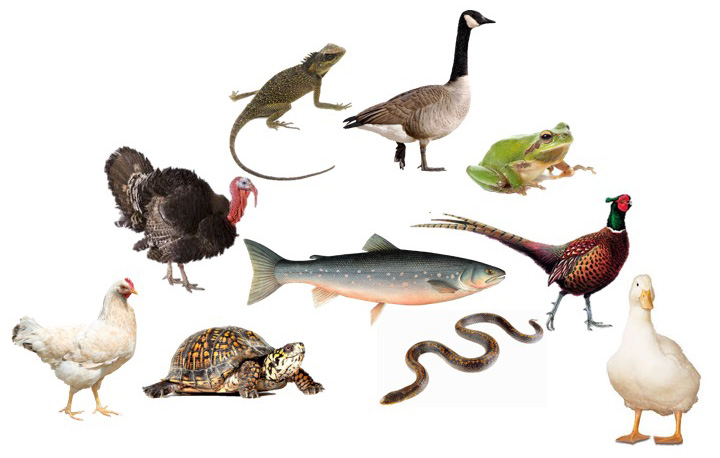

- Display the Animals Who Lay Eggs image for your class to see. Ask students, "What do all of these animals have in common?" Allow students to think and offer answers until they identify that the female of each of these species lays eggs. Clarify that, with some exceptions, most birds, reptiles, and amphibians lay eggs. Each egg varies in size, shape, and consistency (soft or hard shells).

- Ask students to raise their hand if they had an egg for breakfast or any food with eggs as an ingredient in the last 24 hours. All or most students should likely raise their hand. Ask, "What species of animal lays the eggs we typically eat?" (chicken)

- Ask students why we don't typically eat eggs from ducks, turkeys, or other species like snakes or lizards. As students offer answers, provide guiding questions to lead them to think about raising each animal on a farm. Point out that our food is produced on farms, not hunted and gathered. Therefore, our food comes from plants and animals that produce desirable products efficiently. In the case of eggs, efficiency can be measured by considering the size and quantity of eggs the animal can produce compared to the cost of breeding, feeding, and housing the animal. It may be helpful to provide the following statistics for illustration:

- Turkey hens can lay around 100 eggs per year.

- Female geese can lay around 40 eggs per year.

- Female ducks can lay between 60 and 150 eggs per year depending on the breed.

- Chicken hens can lay up to 300 eggs per year.

| Note that each of these numbers represent birds raised on farms where the eggs are collected each day. In the wild, the bird will lay for a much shorter period of time until she completes a nest, often called a clutch. After the clutch is complete, the bird will stop laying eggs and set on them until they hatch. On a farm, collecting the eggs each day causes the bird to continue to lay eggs. Understanding the science of egg laying allows farmers to create the ideal environment to produce the food we eat. |

Elaborate

-

To help students better understand various styles of hen housing, continue with the lesson, Hen House Engineering where students will use the Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning model to evaluate styles of housing used for laying hens in the production of eggs. Using critical thinking skills, students will compare housing styles, determine which system meets their animal welfare standards, and engineer their own hen house model to meet the needs of laying hens.

-

Take a virtual reality field trip to an egg farm that uses enriched colony housing by viewing the 360 video Farm Food 360 Tour - Egg. This video tours a farm in Canada. American egg farms are similar. This video is best viewed using a virtual reality (VR) viewing device, but can also be viewed on a computer, smart phone, or tablet without a VR viewer. VR viewers are available for purchase at agclassroomstore.com.

Evaluate

After completing these activities, review and summarize the following key concepts:

- Photoperiodism is the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night.

- Many plants and animals in our environment, including domestic hens that lay eggs, are impacted by either the presence or absence of sunlight.

- Understanding science, such as the principle of photoperiodism, allows farmers to increase the productivity of their farms to make them more efficient.

Sources

- https://www.incredibleegg.org/about-us/industry-data

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32796704/

- https://www.aeb.org/images/PDFs/Educators/EggProductionCycle.pdf

- https://uepcertified.com/choices-in-hen-housing/

Acknowledgements

Phenomenon chart adapted from work by Susan German.

German, S. (2017, December). Creating conceptual storylines. Science Scope, 41(4), 26-28.

German, S. (2018, January). The steps of a conceptual storyline. Science Scope, 41(5), 32-34.